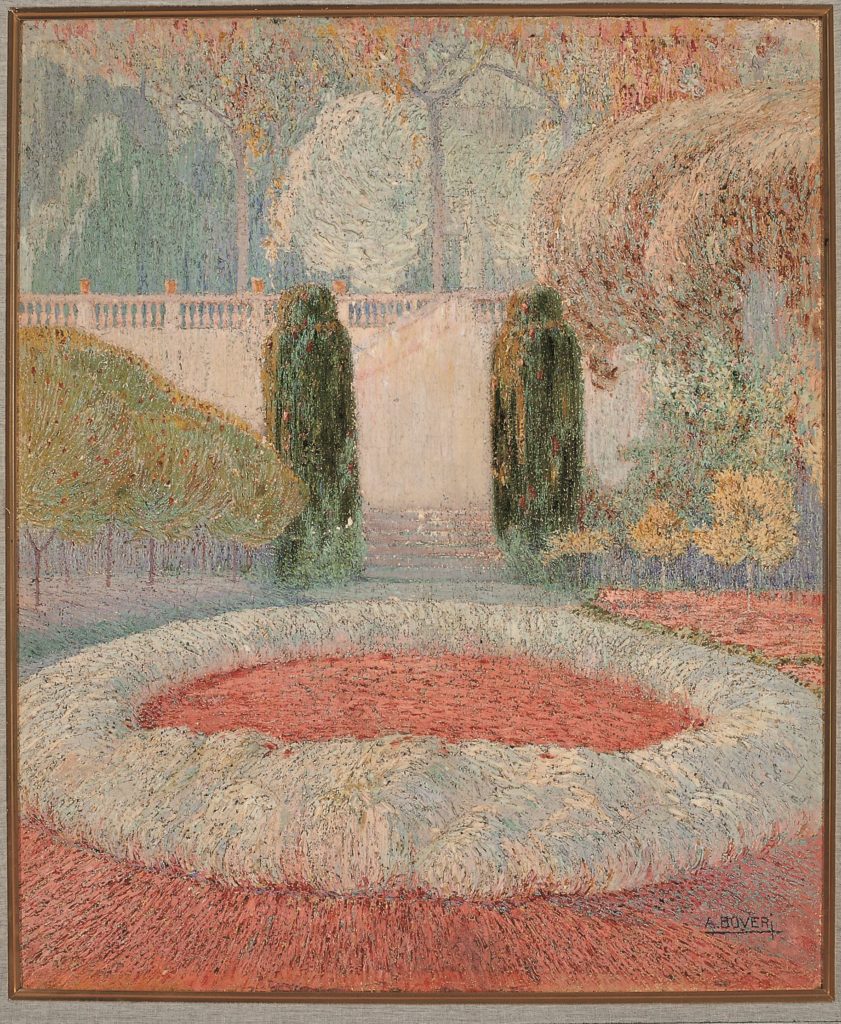

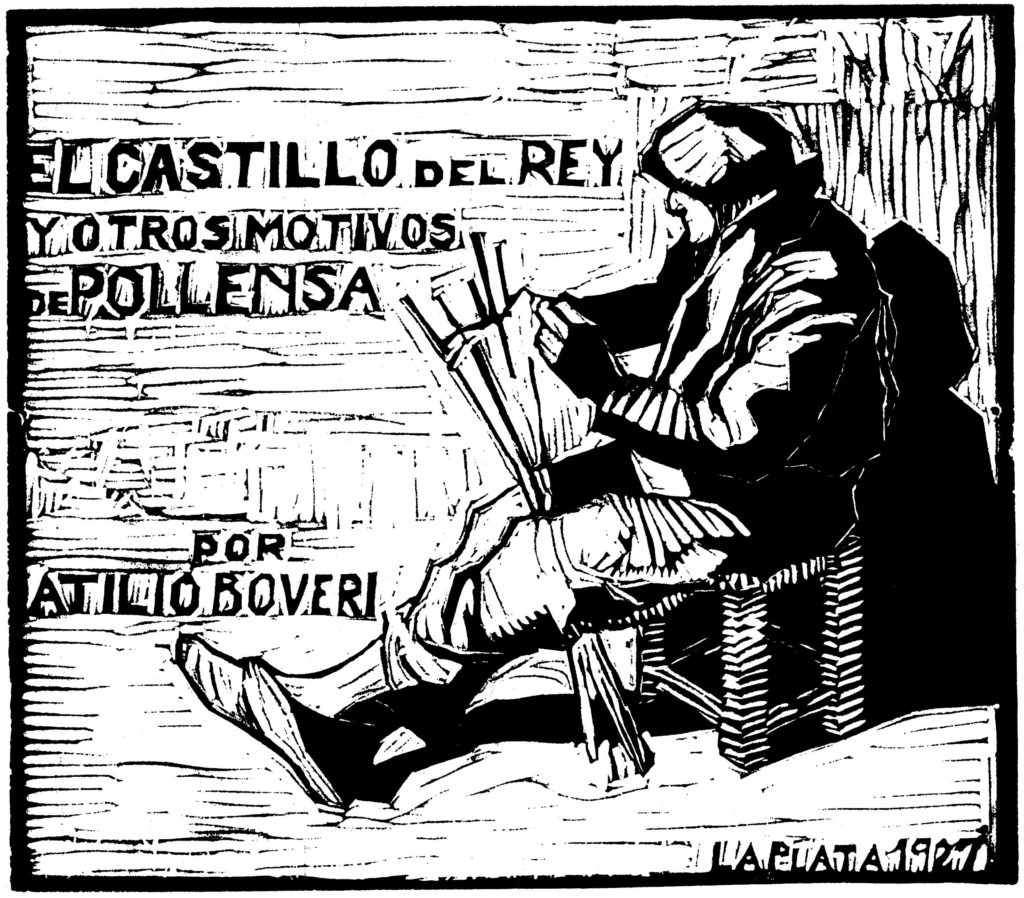

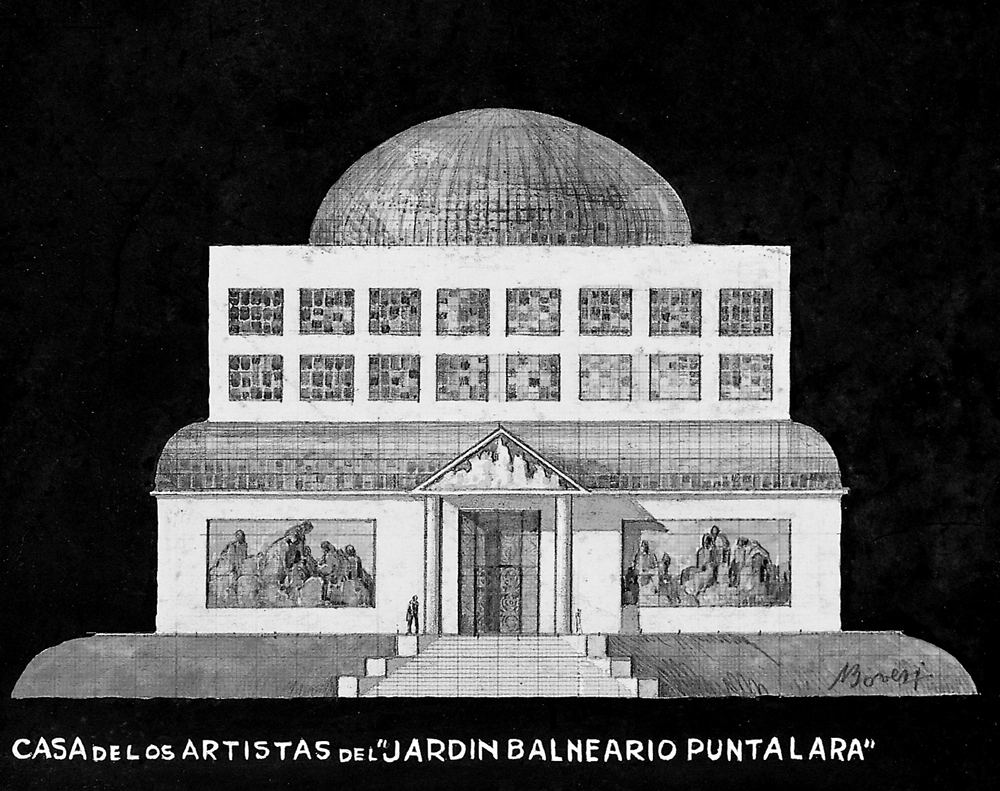

Charo Sanjuán Gómez, a historian and the Director of Aurea Cultura i Art, first discovered the work of the Argentine artist Atilio Boveri (1884-1949) during an extended sojourn in Buenos Aires in the 1990s, while researching the painter Hermen Anglada-Camarasa and other Argentine artists and intellectuals of his circles. It was then that she met the artist’s widow, Elba Cecchini, who had preserved a considerable number of Atilio Boveri’s artistic works, which she later donated to the Museu de Pollença and the Museu de Mallorca. Charo Sanjuán has curated three exhibitions on Boveri at these two museums. She has also written several articles about the artist and has continued to study his life and his work, which includes paintings, drawings, engravings, ceramics, furniture design and decorative murals, as well as architecture, garden design, educational projects, literature and more. It is for this reason that the artist is often described as having a “Renaissance spirit”.

In addition to providing a classification of Atilio Boveri’s vast and diverse body of work, the catalogue, which is now highly developed, will include an in-depth study of his life and production, accompanied by a wealth of abundantly illustrated documents.